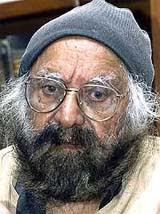

Khushwant Singh has been a towering figure in the field of Indian journalism and literature for more than half a century now, and given the extraordinary amount of publicity that surrounded the release of Absolute Khushwant: The Low-Down on Life, Death and Most Things In-Between, one would have thought that even at the ripe old age of 95 the enfant terrible of Indian letters has many new and exciting things to say. But the book spectacularly fails to live up to the high expectations whipped up by his publishers and the print media before its formal launch.

Despite Khushwant Singh’s claim that he will continue writing as long as someone does not invent a condom for the pen, the sting has definitely gone out of his Cross ballpoint. The Juvenal of post-independence India has no new satires to sing; the Orwellian tone that once characterized his critique of modern Indian society is no longer trenchant. This book, like some others that came before it, contains the same old stuff in a new package. In fact, those who are familiar with Singh’s writing will surely have a feel of déjà vu―certain sentences and passages appear exactly as they do in his earlier books. For several years now, some of his close friends and admirers have competed with each other in bringing out anthologies of his writing and presenting them to the world as though they were fresh products of his factory. After Rohini Singh, Nandini Mehta and Sheela Reddy, it is now Humra Quraishi’s turn. Whether she has done a good job of it or not, we shall come back to the question later.

The present volume records Singh’s various life experiences, his thoughts on how to live, his opinion of some remarkable men and women, and his views on religion, politics and writing. But these are precisely the kind of things we have read before―his stories about Gandhi, Nehru, Indira Gandhi, Sanjay Gandhi, Mother Teresa and Nirad Chaudhuri are pretty well-anthologized. The few paragraphs on Manmohan Singh, Rahul Gandhi and Varun Gandhi that many might consider as new additions to his anecdotal corpus too had figured in the two syndicated weekly columns that he writes.

So, why is it that his popularity has never waned in spite of the fact that all his non-fictional books have become more or less repetitive? He himself admits―without being boastful―that whatever he writes gets published. This frank acknowledgement on his part is the reason behind his enormous success. It is his honesty, transparency and fearlessness which have ensured that he ticks along nicely and have earned him generations of loyal readers.

In the fashion of Montaigne and Bacon (some of the pieces in the collection carry titles, such as, “On Happiness”, “On Work”, “On Honesty”, and “On Death”; thereby making my attempt to compare him with the two celebrated essayists all the more tenable), Khushwant Singh has perfected the art of writing about himself. There is no other living Indian writer who can beat him in this game. At one time it was of course Nirad Chaudhuri who was the greatest practitioner of the autobiographical mode of writing but his prose was most pedantic and he was obsessed with exhibiting his scholarship. On the other hand, it is the directness of Singh’s writing which has touched the correct nerve. Even if one reads an old piece of his, it is never a boring exercise. He certainly knows how to charm the reader. He is the saqi who generously pours his vintage wine into the cups of the drinkers but also knows how to keep the thirst alive in their hearts so that they return to him again and again. More often than not, he has new nuggets to add to the things he has written before. To illustrate, he makes the sensational disclosure that he was cuckolded for twenty-odd years!

Contradiction has been a permanent feature of Singh’s literary architecture. On one page he remarks that his wife was a jealous person and resented his casual meetings with women, and on another he writes that though they sometimes embraced and kissed him in front of her she did not mind at all. But more than textual inconsistencies it is the editorial slip-ups which are an eyesore. The piece that was supposed to speak of his regrets in life concludes as a long diatribe against L.K. Advani. Penguin India and Humra Quraishi should have been more careful.

Although there is nothing splendid about the book, the diverse themes covered in it are integrated by Khushwant Singh’s unique voice and he emerges as an honest, tolerant and humane person who has, in these days of rampant fanaticism, uncompromisingly defended the excellent values of his liberal training.